CASE: A complex presentation, a deferred diagnosis

J. M. is a 25-year-old white nulliparous woman who visits our office reporting pelvic pain. She says the pain began when she was 16 years old, when she was taken to the emergency room for what was thought to be appendicitis. There, she was given a diagnosis of acute, severe cystitis.

Several months later, J. M. began experiencing dysmenorrhea and was given an additional diagnosis of endometriosis, for which she was treated both medically and surgically.

By the time she visits our office, J. M.’s pain has become a daily occurrence that ranges in intensity from 1 to 10 on the numerical rating scale (10, most severe). The pain is mostly localized to the right lower quadrant (RLQ) and is exacerbated by menses and intercourse. She reports mild urinary urgency, voiding every 5 to 6 hours, and one to two episodes of nocturia daily. She has no gastrointestinal symptoms.

We identify four active myofascial trigger points in the RLQ, as well as uterine and adnexal tenderness upon examination. A diagnostic laparoscopy and histology confirm endometriosis, but only three lesions are observed.

After the operation, J. M. is given 5 mg of norethindrone acetate daily to ease the pain that is thought to arise from her endometriosis. Because the pain persists, we add injections of 0.25% bupivacaine at the myofascial trigger points every 4 to 6 weeks. Her pain diminishes for as long as 6 weeks after each injection.

Fifteen months after the laparoscopy, J. M. complains of the need to void every 2 hours because of discomfort and pain and continued nocturia. This time, she experiences no pain at the trigger points, but her bladder is exquisitely tender upon palpation. We order urinalysis and culture, both of which are negative. A potassium sensitivity test is markedly positive, however, confirming the suspected diagnosis of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome.

Could this diagnosis have been made earlier?

J. M. is a real patient in our clinical practice. Her case illustrates the challenges a gynecologist faces in diagnosing chronic pelvic pain. In retrospect, it is apparent that endometriosis was not a major generator of her pain. Instead, abdominal wall myofascial pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) were the major generators. Although her myofascial pain appeared to respond to treatment with bupivacaine, she began to clearly manifest symptoms of IC/PBS.

This article describes the often-thorny diagnosis of IC/PBS and discusses the theories that have been proposed to explain the syndrome. In Part 2 of this article, the many components of management are discussed.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to improve the response to treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. Because the gynecologist is the physician who commonly sees women at the onset of chronic pelvic pain, he or she is ideally positioned to diagnose this disorder early in its course.

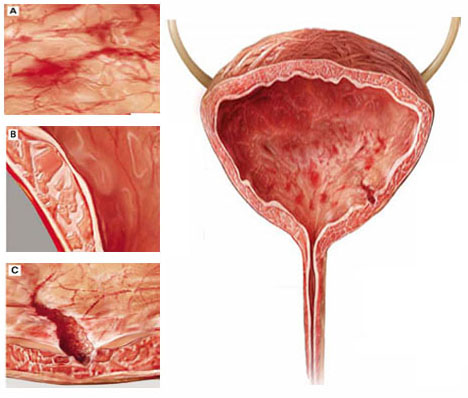

Although interstitial cystitis (IC) occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or malignancy, some pathology may become apparent during cystoscopy with hydrodistention. Potential findings include:

(A) glomerulations, or hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa

(B) damage to the urothelium

(C) Hunner’s ulcer, a defect of the urothelium that is pathognomonic for IC but uncommon.

What is IC/PBS?

This disorder consists of pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder and associated with a persistent urge to void. It occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathology such as bladder carcinoma or cystitis induced by radiation or medication.

The term interstitial cystitis appears to have originated with New York gynecologist Alexander Johnston Chalmers Skene in 1887. Traditionally, interstitial cystitis was diagnosed only in severe cases in which bladder capacity was greatly reduced and Hunner’s ulcer, a fissuring of the bladder mucosa, was present at cystoscopy.1

In 1978, Messing and Stamey broadened the diagnosis of IC to include glomerulations at cystoscopy (FIGURE 1).2 It is now clear that the bladder can be a source of pelvic pain without these clinical findings. As a result, nomenclature has become confusing. Terms in current use include painful bladder syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and a combination of these names. Confusing matters further is the fact that these terms are not always used interchangeably.