For a surgeon, the “frozen” pelvis can be as hazardous as the icy tundra that its name evokes: The reproductive organs and adjacent structures are distorted by extensive adhesive disease and fibrosis, which obscure the normal anatomic landmarks and surgical planes, making dissection extremely difficult and increasing the risk of damage to vital organs.

Despite these very real challenges, few training programs provide gynecologic residents with sufficient surgical experience to operate safely in this setting. The overall keys to success:

- Solid grounding in pelvic anatomy, with live experience involving varying degrees of pelvic distortion

- A realistic expectation that the operation will be difficult and fraught with hazards

- Flexibility to change course when a particular pathway proves too risky

- Patience to take things as slowly as necessary.

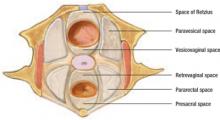

Most important is a retroperitoneal approach—not to mention complete knowledge of the retroperitoneal spaces, where the structures that nourish and support the uterus and lymphatic system lie, as well as the ureters and rectum (FIGURE 1).

It may not be sufficient to learn the anatomy of the pelvis and the steps of the operation from an atlas of surgical technique; “real-life” findings can vary greatly from those described in a textbook. The surgeon needs ample experience to recognize the appearance and tactile characteristics of disease processes that afflict the female pelvis—and to know how to manage them.

FIGURE 1 Areolar tissue fills the pelvic spaces

The pelvic spaces contain areolar tissue and can be exposed by applying traction and deeply placed retractors.

This article describes the challenges posed by the frozen pelvis, so the surgeon can confront the condition with greater confidence and understanding. There is no substitute for hands-on experience, however. Do not begin the operation if you do not think you can complete it. Seek help beforehand, not during the procedure.

Undertake a multipronged diagnostic evaluation

The potential for a frozen pelvis, as well as its causes, can usually be identified by taking a careful history and documenting previous surgeries or pelvic problems (see “Five culprits: Which one is to blame?”).

The physical examination also can be revealing. Be alert for any anatomic changes apparent at the pelvic examination, which should include a rectovaginal assessment. If a lesion is palpated, attempt to define its size and determine whether it is fixed or mobile. Also asccertain whether the cul-de-sac is free, the uterus can be lifted out of the pelvis, and the disease process is predominantly uterine, adnexal, or involves adjacent organs. Although imaging studies may be useful, a careful pelvic examination may yield more practical information about potential difficulties.

Five major causes of extensive pelvic disease lead to a frozen pelvis: infection, surgery, benign growths, malignant growths, and radiation therapy. When evaluating a patient, it is important to determine which of these conditions exist.

Infection. Adhesions and fibrosis secondary to infectious processes such as gonococcal salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, a ruptured diverticulum, infected pelvic hematoma, and ruptured appendix can create anatomic abnormalities.

Surgery. The type of surgery a patient has undergone may provide important clues to potential problems. For example, pelvic distortion that arises from cesarean section and tubal reconstructive surgery differs considerably from that found in women who have undergone abdominal hysterectomy with preservation of one or both ovaries. Removal of a retained left ovary may require extensive dissection of the ureter and bowel.4

Benign and malignant growths. Uterine myomata, endometriosis, and adenomyosis are the most common benign growths that can lead to a frozen pelvis. Malignant growths of the adnexa, such as ovarian carcinoma, can necessitate en bloc resection of portions of the gastrointestinal tract along with the tumor. In contrast, carcinomas of the endometrium and cervix generally do not present with a frozen pelvis, although they occasionally require extensive or radical surgery.

Radiation therapy. When a woman has undergone radiation, pelvic structures are commonly adherent to the uterus and each other, making hysterectomy a challenge. The intestinal and urinary tracts also must be handled with great care. Even a small degree of intraoperative trauma to these structures can lead to postoperative complications including fistula formation.