Human beings are master adapters. Thrust into a hostile environment, or subjected to other overwhelming forces, we quickly adapt to new demands, however harsh they may be. Then we maintain our new skill set with impressive devotion.

And that is the problem: We embrace our skills long after their usefulness has passed.

Gynecologic surgeons are guilty of the same failing. Although we know the vaginal route to be safer, quicker, cheaper, and easier on the patient, 65% to 70% of us still perform hysterectomy using the abdominal approach.1,2

The reason? That was the way we were taught, back in the sometimes hostile years of residency, and no compelling force since has caused us to update our behavior.

Let us not cling to abdominal hysterectomy when a less invasive alternative would be better for the patient. Like the vaginal approach, the laparoscopic route has much to offer. Although some surgical teachers have successfully integrated laparoscopic surgery into their residency training programs, many more opportunities are needed. Applications for laparoscopic fellowships continue to increase in number, largely because young physicians feel their training is deficient in this area.

The time has come to refocus our attention on the alternatives to abdominal hysterectomy, and to learn and perform the least invasive surgical approach whenever possible. This article explores in brief the indications, goals, and basic technique for laparoscopic hysterectomy, and the technological developments that have made it timely and safe.

Indications

As always, a thorough pelvic–rectal examination and evaluation of uterine mobility and vaginal accessibility remain the standard of care for deciding the route of hysterectomy. We believe—as many surgeons do—that the size of the uterus is usually irrelevant when determining the surgical approach.

Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy is indicated when the surgeon needs to remove the uterus and cervix vaginally at the time of other laparoscopic procedures, such as excision of endometriosis, appendectomy, or salpingo-oophorectomy.

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy is warranted when vaginal exposure is inadequate, a large uterus would make the vaginal approach too difficult, the patient has undergone multiple surgeries, or an adnexal mass is suspicious for malignancy.

Supracervical laparoscopic hysterectomy is appropriate when there is normal pelvic support without dyspareunia or cervical abnormalities.

Goals of laparoscopic hysterectomy

For both total and supracervical hysterectomy, the first goal is to secure the uterine vessels (FIGURE 1). This goal can be achieved using a number of tools:

- Electrosurgery with bipolar cautery

- Harmonic energy

- Vascular clips

- Ligating suture

Our preference is to clamp and coagulate the uterine vascular bundle using curved ultrasonic shears (Harmonic Ace).3

Secure the uterine vessels at the ascending branches rather than where they enter the lower uterus, as the latter area is in close proximity to the ureter (FIGURE 2). To ensure hemostasis when using the ultrasonic shears, relax tissue tension and activate the device using minimum power.

FIGURE 1 Secure the uterine vessels

The left ascending uterine vessels are secured using the curved, ultrasonic shears.

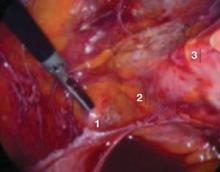

FIGURE 2 Proximity of key structures

Because the ureter (no. 1) and uterine vessels (no. 2) are in close proximity, it is advisable to secure the vessels at the ascending branches (no. 3).

Secondary goal: Identify tissue structures

To identify the 3 levels of tissue structures in the lower pelvis, it is necessary to manipulate the uterus. We recommend learning to use a laparoscopic uterine tissue manipulator instead of a cervical–vaginal manipulator. The former makes it possible to maintain visualization throughout the procedure, obtain adequate exposure, and control tissue tension.

The 3 levels of tissue to be identified are (FIGURE 3):

- Level 1—ascending uterine vascular bundle

- Level 2—junction of the uterosacral–cardinal ligaments

- Level 3—junction of the cervix and vagina

If the uterus is large enough to interfere with visualization of the uterosacral–cardinal ligaments or the cervical–vaginal junction, or both, in situ tissue morcellation is warranted. This debulking should eventually allow visualization of the lower tissue structures.

FIGURE 3 Three levels of tissue

Level 1 corresponds to the ascending uterine vessels, level 2 to the uterosacral–cardinal ligament junction, and level 3 to the cervical–vaginal junction.

How tissue levels come into play

Total hysterectomy. Level 3 is the end-point. Once the uterine vessels are secured and the levels are identified, perform anterior and posterior colpotomy (FIGURE 4). Using traction and counter-traction, coagulate and divide the broad ligament, starting at level 1 and ending at level 3. Perform this step bilaterally.