ObGyns are the first to make the diagnosis and are frequently involved in the treatment of endometrial cancer. It is the most common gynecologic cancer—more common than ovarian cancer and cervical cancer combined.

There will be an estimated 41,200 cases and 7,350 deaths from uterine cancer in 2006.

This update reviews recent studies and practice guidelines that may affect how we manage this disease.

Anticipate cancer when the diagnosis is atypical hyperplasia

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ II, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819.

When we see a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, we need to consider that there very well may be an endometrial cancer already present

ObGyns often manage women with a diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and we know that it is a precursor to endometrial cancer. A now-classic study1 found that 29% of women with complex atypical hyperplasia go on to develop endometrial cancer, and the standard recommendation for women with complex atypical hyperplasia is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (The exception to surgical management is for young women who wish to retain their ability to have children; in these cases, conservative management with progesterone therapy is often attempted.)

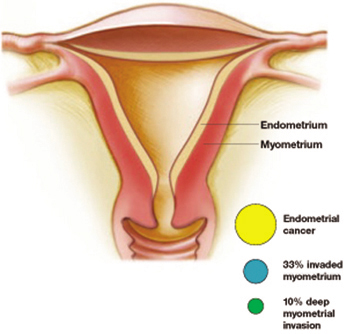

A considerably higher rate—42.6%—of concurrent endometrial carcinoma was found, in a large NIH-sponsored study conducted by Trimble and colleagues, from the Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions. A panel of gynecologic pathologists analyzed the diagnostic biopsy specimens and the hysterectomy slides of 289 women who had a preoperative diagnosis of complex atypical hyperplasia. Of those who had concurrent cancer, about one third of the cancers invaded the myometrium, and about 10% involved deep myometrial invasion.

Atypical hyperplasia: A warning sign

More than 40% of women with a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia had endometrial cancer. About a third of these cancers had invaded the myometrium—a tenth of them deeply. Trimble et al

Practice recommendations

I believe the findings of this study have two important implications for practice:

- When taking a patient with complex atypical hyperplasia to the operating room, an intraoperative frozen section is important. Understaging can occur if the surgeon is not prepared to perform staging.

- In counseling patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, it is important to inform them of the high risk of finding a concurrent cancer. Women who choose conservative medical management with progesterone due to their wish to retain childbearing potential should be informed of the risks. In addition, very close follow-up with serial endometrial biopsies or dilation and curettage should be considered.

No pre-op evidence of metastatic cancer? Don’t get too comfortable

Orr Jr J, Chamberlain D, Kilgore L, Naumann W. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 65. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425.

ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of endometrial cancer cases

The most significant and controversial aspect of the new ACOG Practice Bulletin is the strong recommendation that most women with endometrial cancer undergo full staging, including pelvic washings, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and complete resection of all disease. The exceptions include young or perimenopausal women with grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and women at increased risk of mortality secondary to comorbidities. The bulletin acknowledges that the recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent evidence (Level B).

One of the reasons for full surgical staging for most endometrial cancers is the difficulty in accurately determining grade and depth of invasion intraoperatively. Because of this difficulty, gynecologic oncologists occasionally see patients who were understaged. This limits the oncologist’s ability to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and accurately assess risk of recurrence.

Practice recommendations

Many ObGyns feel comfortable taking a patient with complex hyperplasia or grade I endometrial cancer to the operating room if there is no evidence of metastatic disease or deep myometrial invasion. These new guidelines mean that ObGyns should have a consultant gynecologic oncologist available to perform full staging in the majority of cases of endometrial cancer.

The bulletin also offers helpful guidelines for preoperative evaluation and postoperative adjuvant treatment, and discusses specific recommendations for women found to have endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy, progesterone therapy for early grade I disease, and management of endometrial cancer in patients with morbid obesity.

Estrogen therapy after hysterectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer

Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:587–592.