The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Hear Dr Phillips discuss the key points of this series

With the ranks of the obese expanding, and the severity of obesity increasing as well, obstetricians see a greater percentage of obese and morbidly obese gravidas in their practice. At the end of pregnancy, when it is time to deliver the infant, a number of issues must be taken into account to ensure the safety and health of both mother and child. Part 2 of this two-part article discusses these issues, from intrapartum and intraoperative considerations to care during the postpartum period.

Intrapartum concerns

Induction of labor

Obese women are more likely to require induction of labor; they should be counseled accordingly. The rate of labor induction is as high as 35% in women who have a body mass index (BMI) above 35.1 Many of these inductions are indicated for maternal disease such as diabetes or preeclampsia. However, data suggest that obesity alone increases the induction rate, possibly through increased levels of leptin (an adipokine involved in obesity, appetite, and satiety), which may inhibit uterine contractions.2

Uterine and fetal monitoring

Monitoring of uterine contractions and fetal heart rate can be challenging in obese women. Early use of an intra uterine pressure catheter and fetal scalp electrode can help.

Shoulder dystocia

Obesity is a risk factor for macrosomia, which increases the likelihood of shoulder dystocia. In addition, at least one study supports maternal obesity as an independent risk factor for shoulder dystocia. Women who had a BMI above 30 were 2.7 times more likely to have a pregnancy complicated by shoulder dystocia, after adjustment for macrosomia, diabetes, parity, and induction of labor.3

Because of this risk, appropriate staff should be readily available for assistance, and operative vaginal delivery should be performed with caution, if at all.

Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery

Obese women who have a history of cesarean delivery need to be counseled about the higher risk of failed vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) and the likely need for repeat cesarean delivery. They also need to be told about the elevated risk of infection in the event that VBAC fails.

In women of normal weight, the likelihood of successful VBAC exceeds 80%, compared with a success rate of 68% for women who have a BMI above 29, and 60% for women who have a BMI above 40.4,5

Appropriate counseling and patient selection are critical components of the decision to proceed with a trial of labor in obese women who have a history of cesarean delivery. Twenty-four-hour anesthesia and NICU coverage are also necessary in case emergent cesarean delivery becomes necessary.

Cesarean delivery

Morbidly obese women (BMI >35) have approximately a 50% greater chance of requiring cesarean delivery than do women of normal weight.6 The need for cesarean delivery rises with increasing BMI, probably because of a greater degree of maternal pelvic soft tissue, which increases the risk of both dystocia and cephalopelvic disproportion.

Anesthesia

It may be advisable to place an early epidural in laboring obese patients because they are more likely to require multiple placement attempts and cesarean delivery.

Intraoperative considerations

Ensure availability of the proper equipment

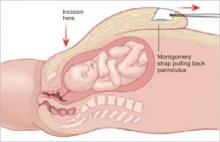

Table extenders, appropriate retractors, and long instruments should be readily available before surgery. For example, obstetricians often retract the panniculus to allow for a Pfannenstiel skin incision ( FIGURE 1 ), which works well to increase exposure. Moreover, the depth of the abdominal wall is much thinner beneath the panniculus.

However, be aware that, even in a supine patient with a leftward tilt, the weight of the panniculus can decrease vena caval return and cause uteroplacental insufficiency and compromised maternal respiration. Cesarean delivery should be performed expediently for these reasons.

A self-retaining elastic abdominal retractor may improve exposure at the same time that it minimizes the amount of retraction that must be exerted by the surgical assistant ( FIGURE 2 ).

FIGURE 1 Retract the panniculus

Retract the panniculus toward the patient’s head and use straps to secure it to facilitate a Pfannenstiel incision.

FIGURE 2 Elastic abdominal retractor improves visibility and access

Insert the inner ring of the adjustable elastic retractor into the abdominal cavity toward the patient’s head until it springs open against the parietal peritoneum. The outer ring is then rolled onto the plastic sleeve until it is snug against the skin.