The author reports that he is a member and past board member of the Iowa Medical Society. He is a current board member of the Midwest Medical Insurance Company.

*This example is a bit disingenuous. In real life, the insurance industry has several mechanisms available to cushion a solitary large outlier like this in any given year (reinsurance, etc). However, the net effect as portrayed here is quite real.

The lessons we’ve learned from past malpractice insurance crises are worth reviewing so we can avoid the next one. In the mid-1970s, it was sky-rocketing malpractice insurance rates—100% to 150% increases year after year. In the 2000–2003 crisis, the number of actual claims fell but the payout per claim soared.

Through these crises, we’ve learned the value of physician-owned malpractice insurance companies, the importance of tort reform (most notably in California), the roles that inflation and technology play, and the need for policing our own ranks to root out incompetent physicians. In this article, I analyze those past crises and the solutions that led us out of them.

That ’70s show

Nobody knew whom to blame for what happened in the 1970s. Attorneys reproached bad physicians and greedy insurance companies. Insurance companies criticized inept physicians and unscrupulous attorneys. We physicians didn’t suddenly become incredibly stupid between 1976 and 1977, but we were at a disadvantage because we didn’t have access to unbiased data to assess the problem.

So state medical societies responded by organizing malpractice liability insurance companies, which became quite successful. This led to the creation of the Physicians Insurance Association of America (PIAA), organized to share solutions and data. These unbiased data have been invaluable in helping us analyze the numerous crises of the past 30 years.

The perfect storm

We analyzed the cause of the late 1970s crisis as the perfect storm: increased severity and increased frequency (see “A glossary of insurance-speak,”). In the 2000–2003 crisis, the severity of claims increased while the frequency of claims actually fell.

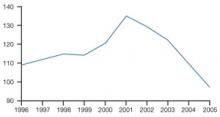

Tracking the combined ratios (losses to premiums) of PIAA companies demonstrates the devastating effects of the crisis years (FIGURE 1).1 Combined ratios around 110, indicating a 10% loss, are tolerable. When the combined ratio inched up to 114 and then skyrocketed, as it did in 2000–2001, crisis ensued.

What this means in real dollars is quite telling. If an insurance company has $100 million income and combined ratios of 120, 134, 129, and 122 over 4 years, the company has lost $105 million (20+34+29+22=105)!

Severity Payout per claim

Frequency Overall number of claims made (for every 100 physicians)

Combined ratio Cumulative effect of expenses, calculated as:

(claims paid + costs)/income from premiums

An insurance company’s goal, of course, is to have income=expenses.

The fix, but not for you

As FIGURE 1 shows, the combined ratios came back into line as the crisis abated—for insurance companies, not physicians.

Insurance companies rectified their combined ratios by raising premiums. If losses rise (numerator), insurance companies can increase premiums (denominator) to bring their combined ratios back into line.

This is healthy for the insurance companies—and you, as an insured, want and need a healthy company—but it is very bad for your pocketbook. Rates increased 105% over 4 years and are likely to stay there until the next crisis, when they will rise even further.

FIGURE 1 10 years’ combined ratio of all PIAA companies 1

The spike marks the 2000–2003 crisis.

That depends on who controls frequency and severity. I will eliminate the “greedy” insurance companies from this discussion. Most physician-owned companies simply return any excess profit to their insured members. Two parties control frequency of claims:

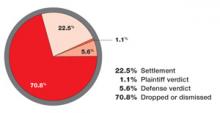

The attorneys. They attempt to develop new theories of litigation and exploit weaknesses in our scientific knowledge. When it’s a bad baby, it must be the doctor’s fault. Lawsuits with no medical foundation remain an expensive problem; 70% of cases nationwide are closed without payment (FIGURE 2).2

The physicians. We are also culpable. In the 1970s, we believed all physicians were going to be sued (mostly true), and that we would all be sued equally (not true). In some jurisdictions, almost one half of all paid malpractice claims come from a fairly small number of habitual offenders.3

FIGURE 2 Outcome of malpractice cases closed in 20042

A large majority of liability cases are closed without payment.