A.G. is a student who misses 2 or 3 days of school each month because of debilitating menstrual migraine (MM) with vomiting. Her referring physician prescribed topiramate, but the drug caused bothersome cognitive effects without relieving her headaches. She is taking a 30-μg oral contraceptive (OC) that contains ethinyl estradiol and drospirenone. Despite starting and stopping the OC several times, she has had no relief. She also takes 100 mg topiramate at bedtime, and 7 to 10 tablets of sumatriptan (100 mg) a month—usually during the menstrual week.

The ObGyn discontinues topiramate and changes dosing of the OC to active pills only for 12 consecutive weeks. During the 13th week, the patient is instructed to take 0.9 mg conjugated equine estrogens twice daily for 7 days before resuming extended-cycle oral contraception. This regimen completely eliminates menstrual migraine. The infrequent migraines the patient does experience—which she attributes to weather fronts—are successfully managed with no more than two doses of a triptan in a month.

A busy gynecology practice sees more migraineurs in a day than a neurology practice sees in a month. But most of the migraineurs who visit gynecology offices have a chief complaint other than headache, and most leave without having mentioned the migraine—returning home to continue treating themselves with the same remedies their mothers used. Many of these women fail to seek a specific diagnosis, or treatment, until they develop chronic daily headaches or become unable to work.

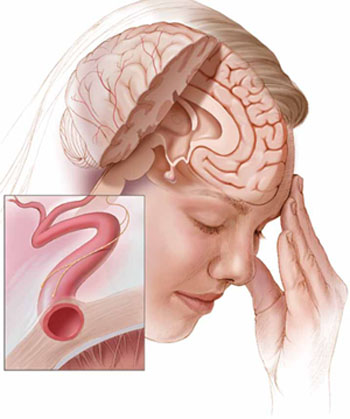

Current theories of migraine implicate spreading cortical depression; trigeminal nerve activation with attendant vasodilation; and neurogenic inflammation.

Menstrual migraine (MM) is, arguably, the most common disabling condition encountered in women’s health. These migraines are more severe, last longer, and are more resistant to treatment than those that occur at other times in the cycle.1,2 And, although headache specialists are adept at diagnosing migraine and prescribing a host of antiepileptic drugs and other migraine preventives, many of these specialists are uncomfortable manipulating the hormonal underpinnings of these “super migraines.”

This article outlines diagnostic criteria, treatment options, and preventive strategies, including hormonal therapy. In the process, it demonstrates how, in many cases, a gynecologist’s expertise in managing hormonal triggers may be the determinant of successful treatment.

Migraine prefers women

Migraine is the most common of all disabling headaches and afflicts 13% of the US population, but with a markedly skewed distribution: It preferentially attacks women in a 3:1 preponderance. The lifetime prevalence of migraine in women is 33%. Migraine strikes women primarily during reproductive years, when many women seek routine health care from a gynecologist rather than an internist or general practitioner.3

Menstrual migraine is defined as migraine without aura that occurs in predictable association with menses. Its onset falls within a 5-day window, spanning 2 days before the onset of menses through the third day of bleeding.5 Although the complete exclusion of migraine with aura from diagnostic criteria is controversial, headache specialists generally agree that aura is uncommonly associated with MM, probably owing to the low-estrogen environment. (Higher concentrations of estrogen are associated with an increased likelihood of aura, similar to the association between estrogen and seizure activity.)

The migraine trigger appears to be estrogen withdrawal in susceptible persons—either during the natural menstrual cycle or as a result of cycling onto inert pills in an oral contraceptive (OC) regimen. A population study found that 39% of menstruating women experience headaches with menses, and almost one third of these headaches meet established criteria for MM or menstrual-related migraine.4

The distinction between these two entities, MM and menstrual-related migraine, is largely semantic. With MM, the menstrual attack is the patient’s only migraine. The broader term implies that she may have other attacks in addition to the menstrual ones. In this article, I’ve gathered both categories under the term MM, which also includes headaches that arise at the time of estrogen withdrawal associated with OC use.

Regardless of what we call them, these headaches have proved to be particularly vexing to headache medicine specialists who hesitate to address hormonal factors.

Diagnostic criteria are clear

Formal diagnosis of migraine requires that at least two of four signature characteristics plus at least one of two associated symptoms be present.5 The four characteristics are: