CASE Postmenopausal dyspareunia

A 60-year-old widow who recently remarried complains of dyspareunia. Examination of the vulva reveals firm but thin white skin over the periclitoral area and labia minora and shrinking of the vulvar skin.

What is the likely diagnosis?

Lichen sclerosus is the probable diagnosis, given her age and the appearance of the vulva, although it is impossible to assure the diagnosis without a biopsy. The preferred treatment is clobetasol, an ultrapotent steroid, applied daily.

True, powerful steroids can cause atrophy if applied regularly to other areas of the skin, but clobetasol does not cause atrophy of vulvar skin. After several weeks of nightly application, the skin should be softer and more pliable, and dyspareunia should be resolved. The patient can then reduce the clobetasol application to twice weekly—but she must continue the treatment indefinitely.

The vulva over the lifespan

The vulva is sensitive to both physiologic and pathologic changes, as well as to the sex hormones that govern the menstrual cycle. The mucosa on the inner aspects of the labia minora is very similar to the skin of the vagina and thus very sensitive to estrogen. The skin of the labia majora and the outer surface of the labia minora is more consistent with hair-bearing skin in the perineal area and more sensitive to androgens, which help thicken the skin. At menopause, the loss of estrogen leads to atrophy, and the vulvar epithelium is reduced to a few layers of mostly intermediate and parabasal cell types. The labia minora and majora as well as the clitoris gradually become less prominent with age.

The skin of the vulva consists of both dermis and epidermis, which interact with each other and respond to different nutritional and hormonal influences. For example, estrogen has little effect on vulvar epidermis, but considerable effect on the dermis, thickening the skin and preventing atrophy.

Postmenopausal atrophic changes can become a clinical problem when a woman resumes sexual intercourse after a long period of abstinence, as in the opening case. If atrophy is the main complaint, estrogen replacement therapy will alleviate symptoms of tightness, irritation, and dyspareunia, but it may take 6 weeks to 6 months to achieve optimal results. In the interim, women need to be reassured that reasonable function can be achieved.

Hygienic considerations

With any vulvar irritation, the patient should discontinue the use of synthetic undergarments in favor of cotton panties, which permit more adequate circulation and do not trap moisture.

Sitz baths often help relieve local discomfort, but should be followed by thorough drying.

The new ACOG Committee Opinion reflects recommendations of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology.17

Vulvodynia. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 345. Obstet Gynecol. October 2006;108:1049–1052.

Vulvar dystrophies: Think “white”

In the past, these diseases have been defined as non-neoplastic epithelial disorders of the vulva. Although there have been many attempts to more accurately define vulvar dystrophies, none have completely described the wide variety of clinical presentations.

In general, dystrophies are disorders of epithelial growth and nutrition that often result in a white surface color change. This definition includes intraepithelial neoplasia and Paget’s disease of the vulva. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease has proposed multiple classifications since 1975. I prefer the clarity of the 1987 classification system.1 I also consider these terms out-of-date: lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, carcinoma simplex, leukoplakic vulvitis, leukoplakia, hyperplastic vulvitis, neurodermatitis, kraurosis vulvae, leukokeratosis, erythroplasia of Queyrat, and Bowen’s disease.

What makes the lesions white?

The white appearance of dystrophic lesions is due to excessive keratin, at times deep pigmentation, and relative avascularity. All 3 of these characteristics are present in the spectrum of vulvar dystrophies. Biopsy of the affected skin is the key to accurate diagnosis and successful therapy.

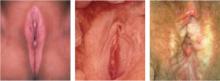

Lichen sclerosus

Does not raise risk of carcinoma

The most common of the 3 groups of white lesions described in the 1987 classification of dystrophies, lichen sclerosus usually occurs in postmenopausal women, but can appear at any age, including childhood (FIGURE 1). Despite claims to the contrary, there is no good evidence that women with lichen sclerosus face a higher risk for vulvar carcinoma.