The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A pregnant woman whose thyroid gland isn’t doing its job presents a serious management problem for her obstetrician. If she has overt hypothyroidism, seen in between 0.3% and 2.5% of pregnancies, active intervention is required to prevent serious damage to the fetus.1,2 Even if she has subclinical disease, seen in 2% to 3% of pregnancies, current research indicates that intervention may be indicated.

Fetal thyroxine requirements increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation, when the fetus is still dependent on maternal thyroxine. A deficiency of maternal thyroxine can have severe adverse outcomes, affecting the course of the pregnancy and the neurologic development of the fetus. To prevent such sequelae, patients who were on thyroid medication before pregnancy should increase the dosage by 30% once pregnancy is confirmed, and hypothyroidism that develops in pregnancy should be managed aggressively and meticulously.

Here, we’ll examine the published research to advise you on evidence-based approaches for diagnosis and management of this complex condition.

Maternal thyroid function

An elaborate negative-feedback loop prevails before pregnancy

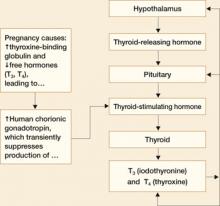

In a nonpregnant woman, thyroid function is controlled by a negative-feedback loop that works like this:

- The hypothalamus releases thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH)

- TRH acts on the pituitary gland to release thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- TSH, in turn, acts on the thyroid gland to release the thyroid hormones iodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) that regulate metabolism

- TRH and TSH concentrations are inversely related to T3 and T4 concentrations. That is, the more TRH and TSH circulating in the blood stream, the less T3 and T4 will be produced by the thyroid gland3

- Almost all (approximately 99%) circulating T3 and T4 is bound to a protein called thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG). Only 1% of these hormones circulate in the free form, and only the free forms are biologically active.3

This relationship is illustrated in FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 1 Thyroid physiology and the impact of pregnancy

Pregnancy reduces free forms of T3 and T4, and increases TSH slightly

Pregnancy alters thyroid function in significant ways:

- Increases in circulating estrogen lead to the production of more TBG

- When TBG increases, more T3 and T4 are bound and fewer free forms of these hormones are available

- Because the total T3 (TT3) and total free T4 (TT4) are decreased in pregnancy, they are not good measures of thyroid function. Maternal thyroid function in pregnancy should be monitored using free T4 (FT4) and TSH levels

- Increased TBG also leads to a slight increase in TSH between the first trimester and term

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations also increase in pregnancy. Because hCG has thyrotropin-like activity, these higher levels cause a transient decrease in TSH by suppression of TSH production between approximately 8 and 14 weeks of gestation.

Fetal thyroid function

During early gestation, the fetus receives thyroid hormone from the mother.1 Maternal T4 crosses the placenta actively—the only hormone that does so.4 The fetus’s need for thyroxine starts to increase as early as 5 weeks of gestation.5

Fetal thyroid development does not begin until 10 to 12 weeks of gestation, and then continues until term. The fetus relies on maternal T4 exclusively before 12 weeks and partially thereafter for normal fetal neurologic development. It follows that maternal hypothyroidism could be detrimental to fetal development if not detected and corrected very early in gestation.

How (and whom) to screen for maternal hypothyroidism

Routine screening has been recommended for women who have infertility, menstrual disorders, or type 1 diabetes mellitus, and for pregnant women who have signs and symptoms of deficient thyroid function.6 In recent years, some authors have recommended screening all pregnant women for thyroid dysfunction, but such recommendations remain controversial.3,7,8 Routine screening is not endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.6

Symptoms overlap typical conditions of pregnancy

The difficulty here is that the characteristic signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism are very similar to physiologic conditions seen in most pregnancies. They include fatigue, constipation, cold intolerance, muscle cramps, hair loss, dry skin, brittle nails, weight gain, intellectual slowness, bradycardia, depression, insomnia, periorbital edema, myxedema, and myxedema coma.6 A side-by-side comparison of pregnancy conditions and hypothyroidism symptoms is provided in TABLE 1.

TABLE 1

Distinguishing hypothyroidism from a normal gestation can be challenging

| SYMPTOM | HYPOTHYROIDISM | PREGNANCY |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | • | • |

| Constipation | • | • |

| Hair loss | • | |

| Dry skin | • | |

| Brittle nails | • | |

| Weight gain | • | • |

| Fluid retention | • | • |

| Bradycardia | • | • |

| Goiter | • | |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | • | • |

Which laboratory tests are informative?

Because screening is controversial and symptomatology does not reliably distinguish hypothyroidism from normal pregnancy, laboratory tests are the standard for diagnosis. Overt hypothyroidism is diagnosed in a symptomatic patient by elevated TSH level and low levels of FT4 and free T3 (FT3). Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as elevated TSH with normal FT4 and FT3 in an asymptomatic patient. Level changes characteristic of normal pregnancy, overt hypothyroidism, and subclinical hypothyroidism are given in TABLE 2.6