The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Despite advances in medicine and surgery over the past century, postoperative wound complication remains a serious challenge. When a complication occurs, it translates into prolonged hospitalization, lost time from work, and greater cost to the patient and the health-care system.

Prevention of wound complication begins well before surgery. Requirements include:

- understanding of wound healing (see below) and the classification of wounds (TABLE 1)

- thorough assessment of the patient for risk factors for impaired wound healing, such as diabetes or use of corticosteroid medication (TABLE 2)

- antibiotic prophylaxis, if indicated (TABLE 3)

- good surgical technique, gentle tissue handling, and meticulous hemostasis

- placement of a drain, when appropriate

- awareness of technology that can enhance healing

- close monitoring in the postoperative period

- intervention at the first hint of abnormality.

In this article, we describe predisposing factors and preventive techniques and measures, and outline the most common wound complications, from seroma to dehiscence, including effective management strategies.

It was pioneering Scottish surgeon John Hunter who noted that “injury alone has in all cases the tendency to produce the disposition and means of a cure.”15

Unlike the tissue regeneration that occurs primarily in lower animals, human wound healing is mediated by collagen deposition, or scarring, which provides structural support to the wound. This scarring process may itself cause a variety of clinical problems.

Wound healing is characterized by overlapping, largely interdependent phases, with no clear demarcation between them. Failure in one phase may have a negative impact on the overall outcome.

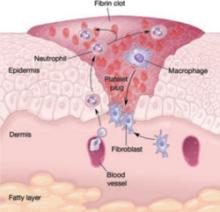

In general, wound healing involves two phases: inflammation and proliferation. Within these phases, the following processes occur: scar maturation, wound contraction, and epithelialization. These repair mechanisms are activated in response to tissue injury even when it is surgically induced.

Inflammatory phase

The initial response to tissue injury is inflammation, which is mediated by various amines, enzymes, and other substances. This inflammation can be further broken down into vascular and cellular responses.

Inflammation triggers increased blood flow and migration of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and other cells into the wound.

The first burst of blood acts to cleanse the wound of foreign debris. It is followed by vasoconstriction, which is mediated by thromboxane 2, to decrease blood loss. Vasodilation then occurs once histamine and serotonin are released, permitting increased blood flow to the wound. The surge in blood flow accounts for the increased warmth and redness of the wound. Vasodilation also increases capillary permeability, allowing the migration of red blood cells, platelets, leukocytes, plasma, and other tissue fluids into the interstitium of the wound. This migration accounts for wound edema.

In the cellular response, which is facilitated by increased blood flow, cell migration occurs as part of an immune response. Neutrophils, the first cells to enter the wound, engage in phagocytosis of bacteria and debris. Subsequently, there is migration of monocytes, macrophages, and other cells. This nonspecific immune response is sustained by prostaglandins, aided by complement factors and cytokines. A specific immune response follows, aimed at destroying specific antigens, and involves both B- and T-lymphocytes.

Proliferative phase

Proliferation is characterized by the infiltration of endothelial cells and fibroblasts and subsequent collagen deposition along a previously formed fibrin network. This new, highly vascularized tissue assumes a granular appearance—hence, the term “granulation tissue.”

Collagen that is deposited in the wound undergoes maturation and remodeling, increasing the tensile strength of the wound. The process continues for months after the initial insult.

All wounds undergo some degree of contraction, but the process is more relevant in wounds that remain open or involve significant tissue loss.

Last, the external covering of the wound is restored by epithelialization.

TABLE 1

Classification of surgical wounds

| CLASS I – Clean wounds (infection rate <5%) |

|

| CLASS II – Clean–contaminated wounds (infection rate 2–10%) |

|

| CLASS III – Contaminated wounds (infection rate 15–20%) |

|

| CLASS IV – Dirty or infected wounds (infection rate >30%) |

|

| SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Surgeons |