Ear, nose, and throat complaints are common even before you superimpose the transformations and demands of pregnancy. Take gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), for example. Experts estimate that one third of the US population suffers from this condition.1 In pregnancy, endocrine and anatomic factors converge to exacerbate acid reflux disorders in 30% to 50% of women.2

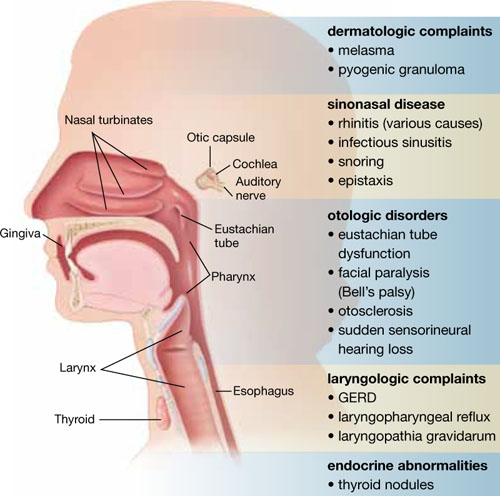

Other complaints, too, surface or worsen during gestation. In Part 1 of this series (August 2010), we discussed sinonasal disease in pregnancy: specifically, pregnancy rhinitis, allergic rhinitis, vasomotor rhinitis, rhinitis medicamentosa, sinusitis, epistaxis, and sleep-disordered breathing. In Part 2, our focus is:

- laryngologic complaints

- – GERD

– laryngopharyngeal reflux

– laryngopathia gravidarum

- otologic disorders

- – eustachian tube dysfunction

– facial paralysis (Bell’s palsy)

– otosclerosis

– sudden sensorineural hearing loss

- endocrine abnormalities

- – thyroid nodules

- dermatologic complaints

- – melasma

– pyogenic granuloma.

Mapping the head and neck, and the spectrum of disease there in pregnancy

This list includes diseases and problems reviewed in the first part of this article, August 2010.

Why does GERD increase in pregnancy?

The smooth muscle–relaxing effects of progesterone and estrogen are likely responsible for the decreased tone of both the upper esophageal and gastroesophageal sphincters. This reduced tone may lead to increased reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus, larynx, and pharynx. Decreased gastric emptying and increased intestinal transit time may also play a role. Reflux of gastric contents may also be exacerbated by compression from the gravid uterus.

Gastroesophageal reflux is physiologic, occurring in healthy people as often as 50 times a day. It becomes GERD when reflux into the esophagus is excessive, causing tissue damage (esophagitis) and clinical symptoms (heartburn). Recent studies suggest that, in addition to the traditional symptoms, GERD is associated with increased severity of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.3

Ultimately, refluxed gastric contents cause mucosal injury to the upper aerodigestive tract. The location of injury and subsequent clinical manifestations are believed to correspond to the pattern of reflux.4

Some refluxers do it in the daytime

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), widely viewed as a separate clinical entity from GERD, is backflow of stomach contents into the laryngopharynx (FIGURE).5 Fewer than 40% of patients who have LPR experience heartburn, and fewer than 25% have evidence of esophagitis.6 LPR patients are predominantly upright, daytime refluxers, whereas GERD patients are predominantly supine or nocturnal refluxers. The threshold for reflux-related injury of the laryngeal epithelium is significantly lower than the threshold for injury to epithelium of the esophagus.7 As a result, even brief reflux exposures can injure the laryngeal epithelium.8

Injury in LPR manifests clinically as posterior laryngeal edema and erythema, obliteration of the laryngeal ventricles, and interarytenoid hypertrophy.5 These changes produce symptoms of chronic throat clearing, hoarseness, cough, and the sensation that something is caught in the throat (globus sensation). History and physical examination are typically sufficient to diagnose LPR.

Lifestyle changes can make a difference in GERD and LPR

Start with simple measures. Advise the patient to elevate the head of her bed 6 to 8 inches. Our patients report that it is usually easier to tolerate books under the legs of the head end of the bed than it is to sleep with extra pillows, especially when a side position is desired.

The patient also should be advised to avoid lying down within 3 hours after eating and to avoid smoking tobacco; drinking beer, wine, coffee, soda, caffeinated tea, and citrus juice; eating foods that are fried, high in fat, or spicy; and using drugs that promote reflux (i.e., calcium channel blockers, sedatives, and nitrates).

An interesting tip: Chewing gum increases salivary bicarbonate production and may neutralize acid.9

Pharmacologic options include H2 blockers and PPIs

Antacids, such as sucralfate, neutralize acid already in the stomach and may have a role in the treatment of acute symptoms.

Histamine 2 (H2) blockers such as cimetidine (Tagamet), ranitidine (Zantac), and famotidine (Pepcid) block the histamine receptor in the stomach and reduce acid secretion by as much as 50%. These medications are typically taken two to three times daily. They all fall into Pregnancy Category B, except for nizatidine (Axid), which is Category C.