- Look for vault prolapse in any woman who has an advanced degree of vaginal prolapse.

- Goals of surgery: to normalize support of all anatomic compartments; alleviate clinical symptoms; and optimize sexual, bowel, and bladder function.

- If sexual function is critical to the patient, a sacrocolpopexy should be the primary surgical option.

- Preoperative low-dose estrogen cream is crucial in most postmenopausal women.

Identifying vault prolapse can be difficult in a woman with extensive vaginal prolapse, and operative failure is likely if support to the apex is not restored.

Because this condition is so challenging to identify, many women undergoing anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy likely have undiagnosed vault prolapse. This may contribute to the 29.2% rate of reoperation in women who undergo pelvic floor reconstructive procedures.1

This article reviews the anatomy of apical support, tells how to identify vaginal vault prolapse during the physical exam, and outlines effective surgical options—both vaginal and abdominal—for its correction. We focus on accurate pelvic assessment as the basis for planning the surgery.

Vaginal stability is fragile

The stability of vaginal anatomy is precarious, since it depends on a series of interrelationships between both dynamic and static structures. When the relationships between the ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault are impaired, vault prolapse ensues.

Thanks to cadaveric and radiographic studies, our understanding of the complexities of vaginal anatomy has improved considerably; still, the area of vaginal support we least understand is the coalescence of ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault.

Grade II prolapse, at least, in 64.8%

An analysis of Women’s Health Initiative enrollees with an intact uterus found that 64.8% had at least grade II prolapse (ie, leading edge of prolapse at –1 to +1 cm from the hymen) according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q).2 Approximately 8% of enrollees had a point D (vaginal apex) of greater than –6 cm, suggesting some degree of vault prolapse.

Hysterectomy appears to contribute. The incidence is about 1% at 3 years; 5% at 17 years.3

In the United States, approximately 30,000 vaginal vault repairs were performed in 1999.

Normal support structure

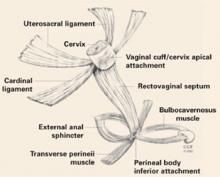

Several support structures coalesce at the vaginal apex. If the cervix is present, it serves as an obvious strong attachment site (FIGURE 1). In hysterectomized women, the structures may lack a strong attachment site, resulting in weakness and prolapse.

FIGURE 1 Vaginal support system

The coalescence of both sets of ligaments forms the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex at the vaginal apex, which is likely crucial to vault support. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

2 sets of ligaments determine support

Uterosacral ligaments—peritoneal and fibromuscular tissue bands extending from the vaginal apex to the sacrum—are the principal support for the vaginal apex, despite their apparent lack of strength.

The role of the cardinal ligaments—which extend laterally from the apex to the pelvic sidewall, adjacent to the ischial spine—is less clear. Since they lie proximal to the ureters, restoring vault support by shortening or reattaching them to the apex is a less attractive option.

The coalescence of these 2 sets of ligaments forms the complex that likely maintains vault support.

In hysterectomized women, locating the attachment of this complex to the vaginal cuff (seen on the exam as apical “dimples”) is key to identifying vault prolapse.

New view of cystoceles, rectoceles

The fibromuscular tissue layer underlying the vaginal epithelium envelops the entire vaginal canal, extending from apex to perineum and from arcus tendineus to arcus tendineus.

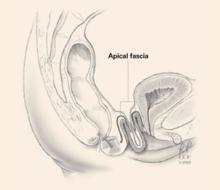

As the aponeurosis does for the abdominal wall, the endopelvic fascia maintains integrity of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. If the fascial layer detaches from the vaginal apex, a true hernia can develop in the form of an enterocele—anterior or posterior—further weakening vault integrity (FIGURE 2).

Reconstructive surgeons are beginning to view cystoceles and rectoceles as a detachment of the endopelvic fascia from the vaginal apex. Thus, it is critical to restore anterior and posterior vaginal wall fascial integrity from apex to perineum by reattaching the endogenous fascia to the vaginal apex, or by placing a biologic or synthetic graft.

FIGURE 2 Apical defects contribute to vault prolapse